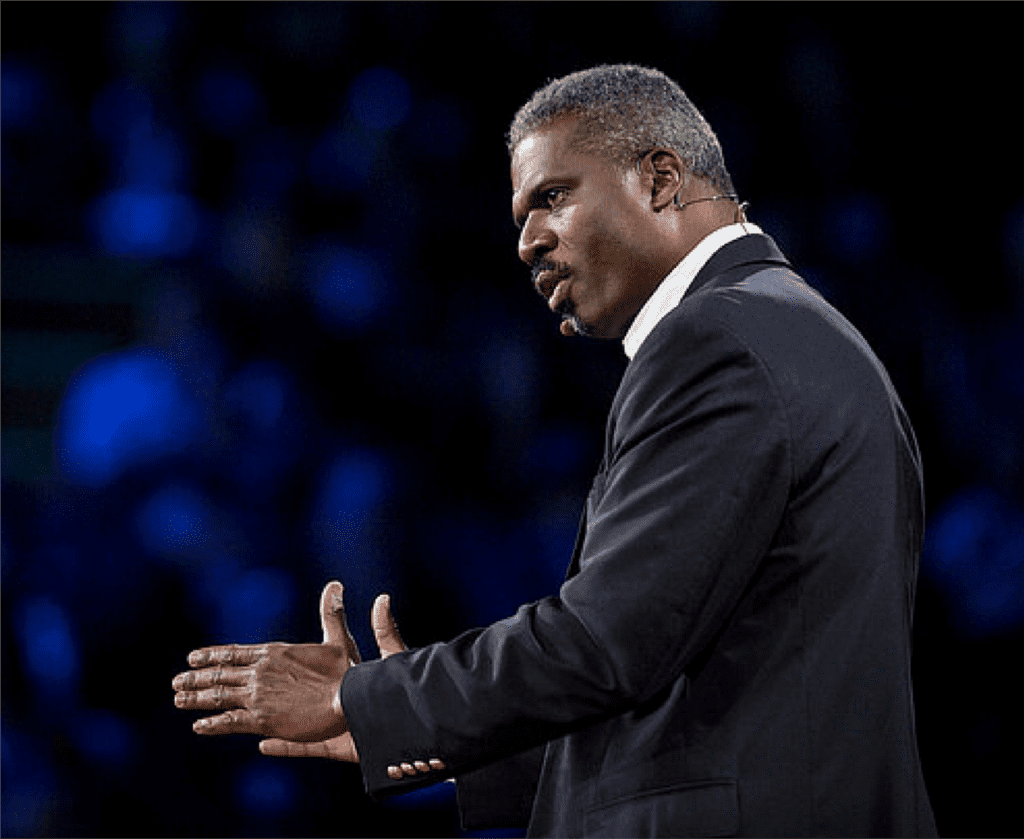

For the past year, I’ve been working with a Baptist minister, Rev. Jeffrey Brown to help him fund and scale his violence reduction work. Rev. Brown has spent the past 25+ years helping Boston and 21 other communities reduce violence. His TED talk tells the story about the The Boston Miracle — a 29 consecutive month period of zero juvenile homicides.

As I learned more about him and his approach, it sounded very familiar. It took me a while to figure out why. Then, one day as I was listening to one of his fascinating stories, it hit me. His approach was nearly identical to the agileapproach to building software/products.

Let me explain. In Boston in the early 1990’s, youth violence was spiraling out of control, as it was in many cities. Police, community and clergy all were trying to combat this toxic trend.

And, what did they do? They did the same things they always tried to do in the past — only more. The police force added officers. They arrested more people. They policed more. Clergy preached about the stopping the violence. They pleaded with their congregants to stop the violence. They preached more. Everyone thought they already knew the answers. They just needed more resources. More time. But, it just wasn’t working.

Then, Rev Brown and a group of other local clergy did something remarkable. They decided to stop preaching and start listening.

Only, there was a problem. The most important stakeholders weren’t in church. They weren’t in school. The gang members themselves were part of a different city, a city at night. So, these clergy decided to start meeting the people of this other city. They started walking around, in groups, unarmed, with no law enforcement backup, at night. They would do shifts from 10 pm to 3 or 4 am.

It took many nights before the gang members and leaders started really talking to them. And, when they did, they were most concerned about whether they were going to be exploited. Why were these ministers, priests and other faith leaders out on the streets at night? Was this another group of people with cameras following them to show everyone how they cared? Were they there to preach? To judge? To snitch?

As time went by and the gang members and other people out on the streets at night started to trust and even expect to see these clergy, something happened.

Gang members, prostitutes, drug dealers started sharing about themselves, their ideas. And, it turns out that 3 things were true:

1. Nobody had ever listened to them before

2. They had great ideas

3. They wanted the same things as everyone else

I encourage you to hear the rest of the remarkable story from Rev. Brown directly via his TED talk or some of his stories atwww.thecouragetolisten.com. There’s also an HBS Case Study about his work. The stories are fascinating, compelling, and timely.

When Rev. Brown and the other members of what became the Ten Point Coalition were staring at an intractable problem, they took a novel and courageous approach. They threw out all of their preconceptions and prejudices and started listening to the real customers and stakeholders.

The faith leaders, armed with only their faith, left their safe sanctuaries, made themselves vulnerable (literally!). They tried things, measured the results and tried again. They began an iterative, empathetic journey.

Here is my summary of some of the lessons from their experiences and success:

- Innovation works best if you have real skin-in-the-game. In order to really listen to customers, you have to be willing to face rejection (or worse). But, without these consequences, it would be too easy to look for the easy, surface answers. If you’re a beneficiary of the product you’re building (i.e. a customer/stakeholder), you’re more likely to get the details right or to keep going until you do

- Look for and invite into the conversation the disenfranchised or under-represented stakeholders. It’s easy to stay comfortable and only speak to people who agree with you or have the same vantage point you do or to go to the same people every time. The customers nobody asks are often sources of the greatest insights. The same is also true of other people who aren’t direct customers, but are stakeholders (users versus buyers, for example). By listening to the actual gang members, they were able to understand the root causes for different types of violent actions. They learned that many were really about retribution and could be prevented

- Think of all of your stakeholders as customers. It would have been easy for the ministers to stay in their sanctuaries. They could have spent their energy preaching more or talking to each other. Instead, they reached out to all of the stakeholders — law enforcement, gang members, drug dealers, teachers, etc

- Be prepared for setbacks by building authentic goodwill. The stakes for the ministers were probably higher than yours. They tried things that didn’t work. But, they built up enough authentic goodwill that they were given a chance to try again

- Look for common goals. It turns out that the gang members, the community and the police all wanted the same thing — less violence and more trust

- You need to adapt as things change. You have to continue to listen to your stakeholders. Every city is different. Every generation is different. And, people change. The same solutions they came up with in 1994 probably wouldn’t work today

- It’s better to ask for forgiveness than permission. Had they asked local law enforcement for “permission” to do their first night walks, they’d have either been talked out of it or had police watching them. It wouldn’t have worked. They knew they were taking a risk. But, they also knew that if they did the same things that had done before that they’d have had the same results

- Be honest with your customers. If you have an ulterior motive or agenda, your customers will figure it out. With the high stakes, the clergy had no room for error on this front

- Customers value consistency and transparency. This was true for the clergy on both sides. They needed to follow through on what they said they’d do. They needed to be there every time they said they would. Their customers were used to being let down

- Figure out what to measure and regularly confirm that you’re still measuring the right things. While there are certainly some obvious metrics — like reduced homicides or injuries, there are also a number of other metrics that are good indicators of current state and predictors of future state. For example, they learned that measuring shots fired is a more immediate way to notice changes than tracking injuries or fatalities

- Staying close to customers helps separate the signal from the noise.The clergy often struggled to decipher the meaning of a new incident. Was this an anomaly or an indication of setbacks? By maintaining their relationships and listening, they were able to distinguish quickly the signal from the noise

- Involve your customers in the solution. It doesn’t matter how good a solution might be, if you have to impose it on your customers, they’re unlikely to appreciate it. When the clergy asked the gang members to be part of creating the solution, they were much more likely to participate and make the solution work

A few months ago, I took an electronic copy of the Agile Manifesto, changed a few words — such as “software” to “violence reduction” and “customers” to “community” — and sent it to Rev. Brown. He looked at it and said “Yup. This is exactly what we did.”

If you’re interested in supporting Rev. Brown as he publishes his book The Courage to Listen about his experiences and lessons and launches his Podcast of the same name, please visit his Kickstarter atwww.kickstarter.com/projects/revjb/the-courage-to-listen or learn more atwww.thecouragetolisten.com.

You can also learn more about our new organization atwww.mycityatpeace.com. We’re building a new funding model for work like this. We invest in real estate and partner with existing investors in areas where we apply Rev. Brown’s approach to reducing violence and improving communities. As violence comes down, property values go up. We use some of these gains to fund our work and keep the virtuous cycles going.